Dr. Philp McMillan, John McMillan

On January 27, 2026, the BBC reported what epidemiologists had long feared: Nipah virus had surfaced again, this time in India’s West Bengal state. Thailand immediately began screening passengers at airports. Two confirmed cases doesn’t sound like much—until you understand what Nipah can do to a human body, and why this particular pathogen keeps public health officials up at night.

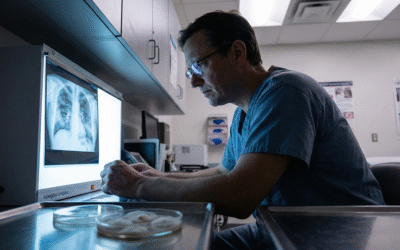

What makes this outbreak noteworthy isn’t just the virus itself. It’s the timing. Eight months before this news broke, Dr. Philip McMillan, a physician and medical commentator, published a detailed presentation titled “Nipah virus, the next deadly global outbreak.” His July 2025 analysis didn’t predict the exact location, but it flagged Nipah as the pathogen most likely to demand our attention next. The alignment between his warning and current events raises questions that deserve serious examination.

A Virus That Kills More Than It Spreads

Nipah first emerged in Malaysia in 1998, traced to fruit bats that had infected pigs, which then infected farmers. The virus earned its fearsome reputation quickly. Its mortality rate sits between 40 and 75 percent—compare that to COVID-19’s roughly 1 percent fatality rate, and the difference becomes visceral. Patients can present with anything from mild symptoms to fatal brain swelling. There’s no vaccine. No specific treatment. When Nipah strikes, doctors can only offer supportive care and hope.

But here’s the thing that has historically kept Nipah from becoming a global catastrophe: it doesn’t spread easily between people. A 2018 study from Singapore examining healthcare workers during a Malaysian outbreak found something reassuring. Among more than 300 healthcare workers across three hospitals who cared for 80 percent of Nipah patients, researchers documented “no reports of any serious encephalitis or hospital admissions.” The virus burned hot but burned out quickly, unable to sustain chains of human-to-human transmission.

This transmission bottleneck has been Nipah’s natural safety valve. Outbreaks flare, kill those unlucky enough to be infected, and then extinguish themselves. Terrible for individuals. Containable for populations.

So why worry now?

A Blueprint That Reads Like a Warning

In 2024, the U.S. National Blueprint for Biodefense ran a simulation exercise. These tabletop scenarios help governments stress-test their response capabilities against theoretical biological threats. The scenario they chose: a Nipah virus attack on Washington D.C. and multiple American cities on Independence Day.

The simulated numbers were grim. The theoretical attack killed 280,000 Americans and infected at least 400,000. Lab confirmation in the exercise pointed to Nipah as the causative agent. This wasn’t prediction—it was preparation. But the choice of Nipah as the featured pathogen wasn’t random. Biodefense planners selected it precisely because of its pandemic potential, its lethality, and the catastrophic consequences should it ever gain the ability to spread efficiently.

Dr. McMillan covered this blueprint extensively in his analysis, connecting dots that others might dismiss as coincidence. “I’m not telling you what is,” he stated carefully. “I’m just sharing with you some ideas based on my observation over many years.”

That measured phrasing matters. This isn’t about jumping to conclusions. It’s about recognizing patterns that warrant attention.

The Molecular Modification That Changed Everything

To understand why Nipah triggers such concern among virologists, you need to understand what happened with COVID-19 at the molecular level.

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that caused the pandemic, belongs to a family of coronaviruses that typically struggle to infect humans efficiently. What made this one different? A tiny structural feature on its spike protein called a furin cleavage site. Think of it as a molecular key that unlocks doors throughout the human body. This single modification, just a handful of amino acids, transformed what might have been another obscure bat virus into a pandemic pathogen capable of infecting cells in the lungs, heart, brain, and gut.

Now apply that lesson to Nipah. The virus already kills most people it infects. Its only limitation is spreading between humans. What would happen if someone—through natural mutation or deliberate engineering—added a similar furin cleavage site to Nipah?

The theoretical outcome keeps biosecurity experts awake at night: a pathogen combining Nipah’s 40-75 percent mortality with efficient airborne transmission. The math becomes apocalyptic quickly.

The Question Nobody Answered

This brings us to the uncomfortable truth at the center of pandemic preparedness: we never definitively determined where SARS-CoV-2 came from.

The wet market theory. The lab leak hypothesis. Years of investigation, political accusations, and scientific debate have produced no consensus. The Wuhan Institute of Virology was studying similar coronaviruses just miles from where the outbreak began. That could be coincidence. It could be something else. We simply don’t know, and the lack of clarity creates a dangerous precedent.

Dr. McMillan frames the stakes bluntly: “If there are people who are willing to alter dangerous viruses so that they can damage the population, if people who did something like that got away with it, I guarantee you they would do it again.”

Whether you believe COVID-19 emerged naturally or escaped from a laboratory, the accountability gap remains. No definitive answer means no definitive consequences. And no consequences means the threshold for future biological events, accidental or intentional, remains troublingly low.

What to Watch For

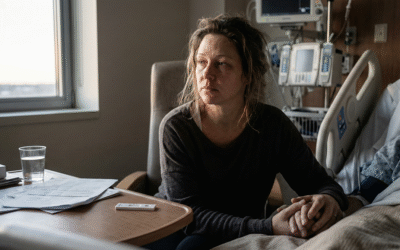

The current West Bengal outbreak will almost certainly follow historical patterns. A handful of cases, tragic for those affected, then the virus will likely burn itself out. That’s the most probable outcome, and hoping for it is reasonable.

But epidemiologists will be watching specific markers. The key indicator: sustained human-to-human transmission. If this strain of Nipah begins spreading efficiently between people, in households, hospitals, or communities, that would break from every documented outbreak in the virus’s history.

Such a pattern wouldn’t prove anything by itself. Viruses do mutate naturally. But it would demand immediate genomic analysis and transparent sharing of that data with the international scientific community. Any strain of Nipah showing enhanced transmissibility warrants scrutiny that goes beyond routine surveillance.

We live in an era where the technology to modify pathogens exists alongside the geopolitical tensions that might motivate such modifications. Recognizing patterns isn’t paranoia. Asking hard questions about unusual disease behavior isn’t conspiracy thinking. It’s the baseline vigilance that pandemic preparedness requires.

The most likely scenario remains a contained outbreak that fades from headlines within weeks. But should something unexpected happen—should this virus begin behaving in ways that defy its natural history—the questions Dr. McMillan raised eight months ago will suddenly feel a lot less theoretical.

As with SARS CoV2 scientists found relative quickly existing drugs who inhibited viral replication. And solved the problem – only due to pharma & politics these medicines were limited available or only illegal available. I am confident that there is also something which works against NIPAH. E.G. I cannot imagine that an early treatment with an i.V. ClO2 cannot oxidize the NIPAH making it incapable to exercise harm. Are we aware of any research going on ?

As with SARS CoV2 scientists found relative quickly existing drugs who inhibited viral replication. And solved the problem – only due to pharma & politics these medicines were limited available or only illegal available. I am confident that there is also something which works against NIPAH. E.G. I cannot imagine that an early treatment with an i.V. ClO2 cannot oxidize the NIPAH making it incapable to exercise harm. Are we aware of any research going on ?