Dr. Philp McMillan, John McMillan

The HBO series “The Last of Us” turned a fungal infection into the stuff of apocalyptic nightmares, with cordyceps spores transforming humans into zombie-like creatures. The show was fiction, but it drew on a real anxiety: fungi are ancient, opportunistic, and far more dangerous than most people realize. They tend to stay in their lane, kept in check by healthy immune systems. When they break loose, something has gone terribly wrong.

A 70-year-old construction worker in California recently learned this the hard way.

He walked into an emergency room with a painful ulcer on his nose and a fog of confusion clouding his mind. He had spent half a century building things in the Central Valley, breathing in dust and desert air. He had no HIV. He was not on chemotherapy. He had no known immune disorder. And yet, somehow, a fungal infection had spread from his lungs to his skin to his brain.

This is the kind of case that makes physicians pause. Disseminated coccidioidomycosis, commonly known as Valley Fever, affects roughly a third of people who inhale the fungal spores endemic to the American Southwest. But only about 2% ever see the infection escape their lungs and colonize other organs. Those who do are almost always profoundly immunocompromised. This man, on paper, was not.

So what went wrong?

According to Dr. Philip McMillan, a physician who has spent years analyzing COVID-19’s long-term effects, the answer may be hiding in plain sight. His close reading of the BMJ case report, published in December 2025, points to a pattern he has seen before: an immune system thrown into quiet chaos by a virus that was never formally diagnosed.

A Timeline of Warning Signs

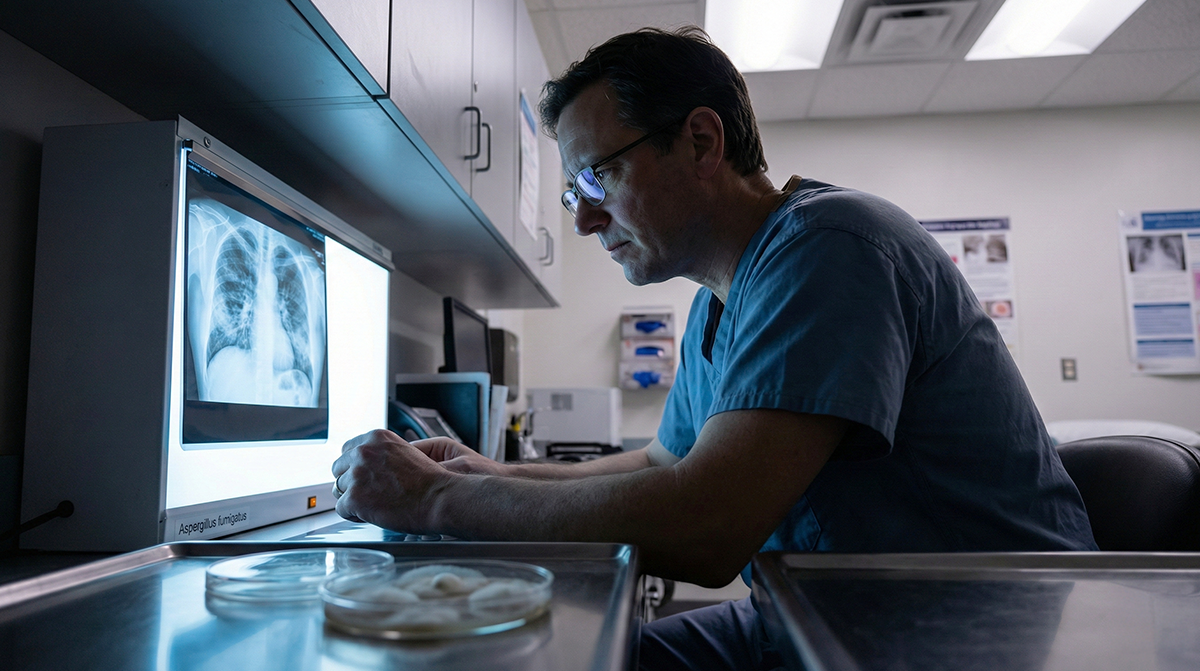

Months before the emergency room visit, the patient experienced low-grade fevers and chest discomfort. A CT scan revealed bilateral ground glass opacities, a hazy appearance in both lungs that suggests inflammation or scarring, along with consolidations and fluid buildup around the lungs. He was treated for a bacterial infection, *Haemophilus influenzae*, and his respiratory symptoms cleared.

Then came the nasal papules. Then an ulcer. Then confusion.

By the time physicians identified the fungal culprit, it had already formed an abscess in his brain.

What stands out about this progression is not the fungal infection itself, but what preceded it. Bilateral ground glass opacities are a radiological hallmark of COVID-19 lung damage. During the early pandemic, clinicians could often diagnose COVID from a chest scan alone, even before symptoms appeared. The pattern in this patient’s lungs fits that profile, and yet COVID was never mentioned in the case report. No test. No vaccination status. No consideration whatsoever.

The Immunological Puzzle

When the medical team ran a lymphocyte subset analysis, a blood test that breaks down the different types of immune cells, they interpreted the results as showing preserved immune function with normal age-related decline. A closer look suggests otherwise.

The numbers tell a different story. The patient’s lymphocyte count was low, a condition called lymphopenia. His B cells, which produce antibodies, were depleted. So were his natural killer cells, the immune system’s first-line patrol against viruses and tumors. His central memory CD8 cells, critical for long-term immune memory, were also diminished.

And yet other compartments were elevated. CD4 T cells, which coordinate immune responses, were higher than normal. So were certain CD8 effector cells. This is not the picture of a weakened immune system. It is the picture of a dysregulated one: some components overactive, others depleted, the whole system out of balance.

This pattern is consistent with what some researchers describe as a “subclinical cytokine storm,” a state in which the immune system, triggered by persistent or recent COVID infection, begins targeting itself. The result is a functional immunodeficiency that standard tests can miss.

The Diagnostic Blind Spot

The medical community has largely moved on from COVID-19 as a diagnostic priority. If a patient tests negative, the virus is ruled out. But this approach may be dangerously incomplete. COVID, some argue, should be a clinical diagnosis, one made by recognizing patterns, not just reading swabs.

The patterns to look for: persistent lymphopenia that outlasts the acute infection phase. Bilateral lung infiltrates that linger. Unusual disease progression in patients who should be immune-competent. Treatment failures that defy explanation.

This patient had all of them.

The man himself seemed to sense that something was being missed. In a statement included in the case report, he reflected on his experience: “I feel that testing for valley fever should be included as part of the protocol for patients presenting with symptoms similar to pneumonia, COVID-19, and influenza.”

He had connected the dots. His medical team had not.

Persistent Damage, Persistent Questions

Ten months of antifungal therapy brought the patient back to his normal activities. The brain abscess resolved. But follow-up imaging told a more complicated story. His lungs still showed ground glass opacities. Bilateral pleural effusions, fluid around the lungs, persisted.

These findings likely do not represent ongoing fungal disease. If they did, the patient would be far sicker. Instead, they may reflect post-COVID pulmonary scarring, damage that lingers long after the virus has cleared.

The patient now faces lifelong antifungal therapy, a precaution against the infection returning to his brain. But if the underlying immune dysregulation is never addressed, he may remain vulnerable to other opportunistic infections, or worse.

Clinical Vigilance

The implications extend far beyond one man in California. If COVID-induced immune dysregulation is causing cases like this to slip through the diagnostic net, how many others are being missed?

The message to clinicians is blunt: “If we continue to just treat things as we did pre-pandemic, many people are going to suffer. Many more will die.”

Six years into studying this virus, researchers acknowledge there are still pieces that do not fit. But the clinical community must start looking backward, at the autoimmune and dysregulation patterns that COVID leaves in its wake, before it can move forward effectively.

For patients and their families, the takeaway is simpler. Ask questions. If symptoms do not resolve with standard treatment, if patterns seem unusual, if something feels off, push for deeper investigation. The immune system is complex, and COVID has made it more so.

Unlike “The Last of Us,” this story does not end with civilization collapsing. But it does end with a warning. Fungal infections are not supposed to spread like this in healthy people. When they do, it is worth asking what invisible damage came first.

0 Comments